Author: Pat Brien

Legendary film-maker Alan Clarke must have flipped out when he first saw the youthful Ray Winstone whilst searching for a powerful, intelligent lead for his shocking, brutal account of life in a British young-offenders’ institution, ‘Scum’. (1977). Winstone said that at the time he had no idea what he was supposed to be doing, or if he wanted to be an actor, and gave Clarke full credit for drawing out of him his brilliant portrayal of a brutal, violent, but highly intelligent young man trapped in a no-win situation.

The project constituted a huge effort on Clarke’s part, commissioned by the BBC and promptly dropped the moment the BBC higher-ups saw what they had green-lighted. No stranger to controversy, Clarke responded by turning the TV-film into a movie of the same name (1979), and the rest is British cinema history.

One of the many people influenced by ‘Scum’ was Tim Roth, who, although already building a career on the stage, remained obsessed by the idea of film-acting and was given his big break by Clarke himself in another stunning piece of social commentary ‘Made In Britain’ (1983). Again, it was excellent casting on Clarke’s part, providing the director with the perfect lead, just as it was an excellent opportunity for Roth, who was provided not only with the perfect character, but the perfect teacher.

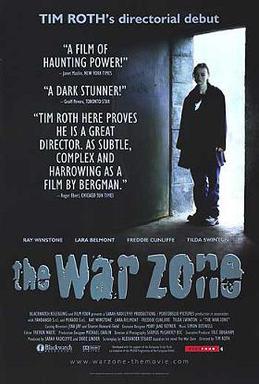

Thirteen or fourteen years later, when Roth started directing his own movie ‘The War Zone’ (1999), based on the book by Alexander Stuart, he applied a sense of integrity to subject and a brutal directness that almost certainly came from Clarke. But he also showed an individuality in his approach to film-making that I imagine Clarke would have been proud to see; just as he would have been proud to see his other discovery, Ray Winstone, turning in such an amazing, ground-breaking performance. I don’t believe that the movie-going public will ever get another chance to see Ray Winstone—or anybody else for that matter—portray a character so unthreatening, so likeable, or so evil as the father in ‘The War Zone’.

I was stunned by ‘The War Zone’. Having no idea what the story was, I at first thought that I was watching a warm-hearted family drama about a family moving to an isolated Devon farmhouse from London, and was surprised by how affable and gentle Ray Winstone seemed in the role of loving father.

Then things turned. The relentless bleakness and isolation of the winter Devon countryside is used by Roth for a reason, and the sense of each character’s isolation soon starts to grow. The film focuses on the fifteen year old boy, Tom, whose sexual awakening is becoming confused; who is disturbed by his feelings towards his attractive sister, eighteen year old Jessie; and who seemingly starts to transfer his guilt by snarling accusations to her about the nature of her relationship with their father.

Roth doesn’t reveal too much to the audience during these scenes. Instead, he invites us to sit uneasily in the dark corners of other people’s lives and nervously watch as paranoia, confusion, sexual desire, and vile, hidden truths begin to lock together in a dark, impenetrable vortex and spin hellishly out of control.

Tom finds photographs of Jessie and her friend undressed, laughing and playing around; but one photograph shows the father with Jessie, his arm around her naked form, one hand covering a breast. It should be evidence, but so many scenes come before it showing the family around each other whilst in a state of casual undress, that there is room for doubt as to what it implies.

Soon after, Roth hits his audience with a wake-up call of seismic proportions as Tom follows Jessie and his father to an isolated bunker on the Devon coastline and watches a brutal act of incestuous rape. Roth doesn’t spare us. In a way, he punishes us with the truth; shoves the audiences’ faces in it and makes them live the ordeal. It’s a moment of true cinematic agony; a moment in hell that purges all stereotypes about sexual abusers and exposes the terrible reality that a monster can be anybody. The fact that there are parallels in this film to some of the classier psychological horror films—in terms of look and atmosphere—is no accident. It is a brilliant, calculated move.

Many films and TV shows dealing with this topic do so by presenting a character who, to the outside world, comes across like the stereotype of a second-hand car-salesman: all smarm and charm and fake sincerity; but who, as soon as the front door is closed, turns into a monster who starts terrorising his family.

What is truly worrying about this film is that Ray Winstone’s character convinces the audience that he genuinely loves his family—or that he believes that he loves his family—not just before the rape scene, but after it. But, because of the brutality of the rape scene, the audience is shocked into seeing that the father’s warmth and concern is really nothing more than sentimental self-indulgence; the gross selfishness of a man capable of true evil.

Near the end of the film, as the father screams his horrified, outraged denials, you realise—to your own horror—that without that bunker scene you would almost certainly have started questioning the facts behind Tom’s crucial photograph, as well as the stability of Tom’s personality.

It is art—the real thing—and should not be dealt with as entertainment just because of the medium through which it is presented. It is powerful; and the fact that Roth approached the film from a cinematographic perspective rather than a cold, documentary perspective, adds a huge amount of power.

Rather than create a sense of distance and objectivity, he draws you in emotionally, shoves you in with Jessie during the agony of the rape; leaves you in a room with her and Tom as she burns herself with a cigarette, then invites him to burn her; plays on your mute helplessness as the boy takes her up on her offer, because she is as guilty in his eyes as she is in her own. And because he is jealous.

When you leave the dark room of the cinema, you take the dark rooms of that family’s life with you. You know that you have shared somebody’s reality and you try to deal with that by going over details instead, considering the brilliant duality of some of the scenes, one of which leaves you wondering if you were watching an innocuous family argument or a perverse outburst of jealousy on the father’s part.

Just as stunning as the subject matter itself was the revelation by Tim Roth—in answer to one of the many questions from which I built this article—that two of the crucial roles (the abused eighteen year old daughter, Jessie, played by Lara Belmont, and the brooding fifteen year old Tom, played by Freddie Cunliffe), were played by first-time actors.

I remember staring at Roth, shocked, and announcing: “But that’s a huge risk, considering the material.” Roth admitted that it had indeed been a huge risk, but one that had paid off brilliantly. And I couldn’t argue with that.

Watching Lara Belmont and Freddie Cunliffe matching the likes of Ray Winstone and the superb Tilda Swinton as mother to Jessie, Tom, and a newborn child (in real life, Swinton had just given birth to twins and used her body to make the realism in what we were seeing all the more convincing), was a revelation, and a personal triumph for Tim Roth as a director.

What Roth proves in such an artful way through this film is that one of the great problems in sexually abusive situations is the inability of adults to face up to the reality of what is going on. Unanswered questions about the health problems of the baby indicate that unless such things are faced up to, they will not only continue, but develop and spread.

The night after the screening of ‘The War Zone,’ at a screening of Alan Clarke’s last film ‘Elephant’ (1989), along with the screening of the original TV version of ‘Scum,’ Tim Roth and Ray Winstone again appeared on stage, this time with Molly Clarke, Alan Clarke’s daughter, to talk about the great man’s influence on their lives and careers. I kept thinking of Roth’s movie; of Ray Winstone’s performance in it; and of how proud Clarke would have been of them for making it.

Of course, that would have sounded far too showbiz to actually say out loud, so I kept my big mouth shut for once and contented myself with the knowledge that the Paris Cinema Festival has been a huge success, showing not only cinematic brilliance but also artistic integrity and a desire among film-makers to still use their art to make statements, instigate changes, and to do the right thing.

The Seventh Art is alive and well.

END NOTE: At the time of release Roth’s film picked up awards for ‘Best New British Film’ at the Edinburgh Film Festival; ‘The Cicae Award’ at the Berlin Film Festival; ‘Best Of First Works’ at the Troia Film Festival; ‘Best Newcomer’ (Yes!) for Lara Belmont, at The British Independent Awards; and a ‘Director’s Award’ at the European Film Awards.

Pat Brien is British and has had countless articles published in various independent magazines in England, as well as several literary short-stories and a dramatic monologue broadcast on BBC radio.

One of his literary stories has just been published in the United States, in the annual literary journal ‘The Long Story,’ and one of his screenplays recently reached the semi-finals of Francis Ford Coppolla’s American Zoetrope Screenplay Contest.

His poem ‘Genetically Modified Food For Thought’ has also just been accepted for publication in the next edition of the New York/Paris poetry journal ‘Van Gogh’s Ear.’ He lives and works in Paris, France.