Published May 20, 2021

Artist? Hustler? Schemer? Dreamer?

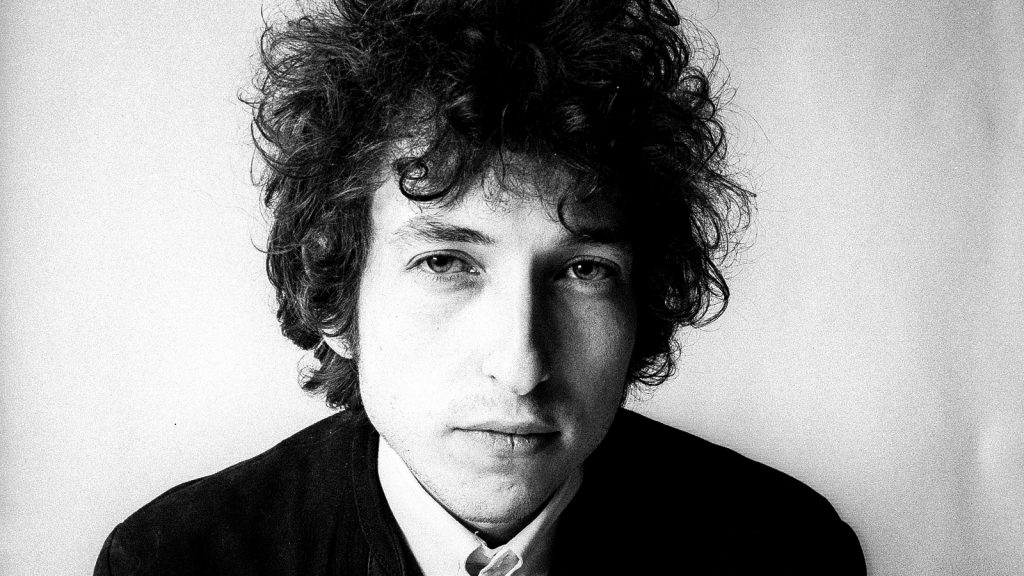

Bob Dylan’s controversial career as a singer/songwriter made him the icon of a generation, a reluctant recipient of the Nobel Prize in Literature, and an almost mythical being.

Known to confuse facts and fantasy about himself as readily as anybody who ever spoke or wrote about him, he is an enigma, with many detractors and millions of admirers.

So what can we learn about – and from – Dylan’s career?

Let’s take a look.

1. Was Dylan’s early image a fraud?

Yes and no. Before his 20th birthday, Dylan was singing for free at Gerde’s Folk City “Hootenannies” in Manhattan.

Originally rejected for looking too young, he caused a stir from the outset.

A teenager with puppy fat singing folk and blues songs about hard-travelling, lost loves, and hoping only for a clean grave to sleep in, Dylan was working strictly against the odds from a career perspective.

So what happened?

It’s tough to choose between “self-belief” and “self-delusion”. When Dylan sang adult themes, usually in the style of Woody Guthrie, his pained vocalizing created an air of authenticity that wowed people. He appeared to be living the image.

Then came strategy.

Before people could absorb the contradiction between songs and singer, Dylan would break into a humorous number, becoming the star of the song — a Charlie Chaplin character — who everybody fell in love with.

Including folk critic for The New York Times, Robert Shelton.

2. Is Dylan a plagiarist?

No — Dylan came from a folk tradition in which a traveling “guitar picker” would hear a song, remember the tune, then add words.

When “Big John” Hammond signed Dylan to Columbia, Hammond was legendary as a jazz producer and the discoverer of Billie Holiday. He signed Dylan on instinct.

Their first album contained two original Dylan songs and didn’t sell.

This was a controversial career move for Hammond himself. Dylan quickly became known as “Hammond’s Folly”.

That ended with the release of Dylan’s second album, “The Freewheelin’ Bob Dylan”.

The album was crammed with Dylan classics like “Blowin’ in the Wind” “Girl From the North Country” “Don’t Think Twice, It’s Alright” and “Masters of War”.

And it sold.

Dylan’s new manager, Albert Grossman, gave “Blowin’ in the Wind” to one of his other groups, “Peter, Paul and Mary” who had a huge hit with it.

Dylan the songwriter had arrived.

With his album “The Times They Are a Changin’” came trouble. Dylan’s song “With God On Our Side” used the same melody as Dominic Behan’s Irish rebel song, “The Patriot Game”.

Behan was outraged, until a music expert pointed out that Behan himself had taken the melody from another song, in line with folk tradition.

It’s hard to know how seriously Dylan took this.

Even today, fans love picking out uncredited quotes on Dylan albums, from classic literature and poetry to Clint Eastwood movies.

Fans say Dylan loves to drop literary and cultural “clues”, while detractors call it plagiarism, plain and simple. But there’s nothing plain or simple about Dylan.

Including his huge career risks.

3. Did Dylan “sell out” for money?

The accusation doesn’t add up. It’s well documented that Dylan’s first love was rock ‘n roll – it’s what he first played, before discovering Woody Guthrie and going a different route.

He also became disenchanted with the folk “protest” scene. Even his early albums brought criticism from folk contemporaries, claiming he kept moving into “personal” songs, rather than sticking to politics.

Dylan reacted with an album that cried out for electric music and moved closer to Rock ‘n Roll, with a record-company title he despised: “Another Side of Bob Dylan”.

One of the songs “My Back Pages” lamented his recent political past, declaring:

“Ah, but I was so much older then/I’m younger than that now.”

Dylan was fascinated by how The Beatles were changing Rock ‘n Roll; and angry that Americans weren’t doing more to compete with “The British Invasion”.

It’s no coincidence that Dylan’s next, half-electric album, was titled: “Bringing It All Back Home”.

Also, Dylan’s first electric single was hardly a surefire hit.

Mixing skip-rope and/or oldie scat song rhythms with lyrics about drugs and the emerging counterculture was a far cry from pop culture in early 1965. (And would stay that way until the emergence of rap.)

Influenced by Guthrie/Seeger’s ‘Taking It Easy’ and Chuck Berry’s superb use of this traditional style: ‘Too Much Monkey Business’, Dylan stripped down any commercial distractions or considerations, making only the relentlessly driving form and biting social commentary the stars.

Jack Kerouac’s brooding beat vision was also an unhidden influence.

Dylan was taking a huge risk with his reputation and career.

Which included isolating his audience. The folk purists went berserk when Dylan plugged in an electric guitar, and took to following him to concerts just to boo and create problems.

The planned move to full electric also threatened the many cover versions of his acoustic songs, from which he made big money as songwriter – on top of his own record sales.

However, despite or because of its originality, “Subterranean Homesick Blues” hit the Top 40 in the US and the Top 10 in the UK.

Dylan’s gamble had paid off. Or had it?

One of Dylan’s acoustic songs from Bringing It All Back Home, “Mr. Tambourine Man” was covered by The Byrds and hit #1 in the US and UK; other covers by the group cemented Dylan’s money-making success as a songwriter for others.

But his plan didn’t change.

A single from his fully electric followup album, “Highway 61 Revisited” was over six minutes long – unheard of at the time. The song, “Like a Rolling Stone” was also an explosion of searing anger and pain.

The song was so long and so angry that Dylan’s record company didn’t want it released.

Luckily, an acetate of the song fell into the hands of some influential DJs and rock journalists, who put pressure on the company until they relented.

“Like a Rolling Stone” hit the #2 spot on the US Billboard Hot 100 and was a top 10 hit in many countries, changing popular music.

It also inspired The Beatles to ramp up their songwriting and experimentation.

Ultimately, it was voted #1 on Rolling Stone magazine’s list of “The 500 Greatest Songs of All Time.”

4. What career lessons can we learn from Dylan?

When Dylan believed in something, he lived it unabashedly. What the “rules” were and what others thought meant nothing.

Dylan never stuck to a “winning formula”; instead he followed his vision, experimented, and stayed true to himself.

Between 1961 and 1965, Dylan built and risked destroying his reputation and career. In the years that followed, he repeated that many times.

So how do we make sense of this?

Let’s allow the great man to define career success himself:

“When you get out of bed in the morning, go to bed at night, and – in between – do whatever it is you want to do, that’s success.” — Dylan.

Sources: No Direction Home: The Life and Music of Bob Dylan by Robert Shelton – published by William Morrow/Beach Tree Books, New York, 1986; Bob Dylan by Anthony Scaduto – published by Abacus, 1972; Chronicles Volume One by Bob Dylan – published by Simon & Schuster, New York, 2004.